Deconstructing Colonial Myths (or Fuck the Colonial Myths) - Part One: Roads, Railways & Civilization

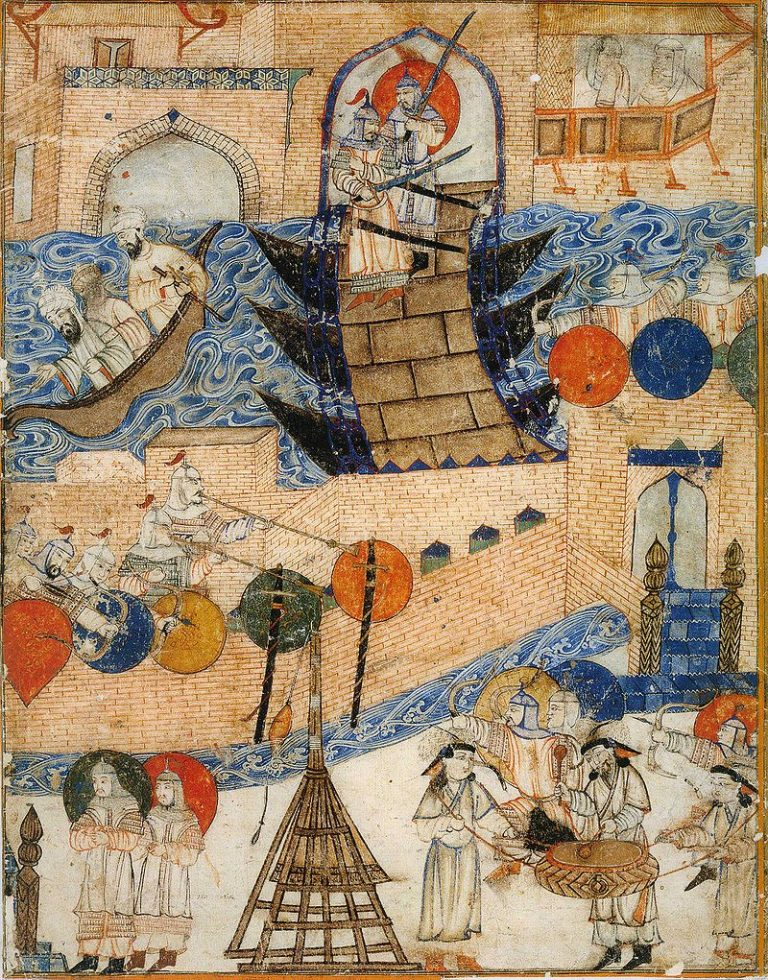

We continue to hear it – apologies for colonialism, justifications for colonialism, legitimations for colonialism. Fuck it all. Some – like providing civilization, infrastructure and technology – are contemporary justifications that propagandize colonial history and legitimate the consequences of that history; while others are historic justifications that legitimated colonialism’s brutality in the first place – from funding further Crusades, to narratives about combating

Oct 25, 202520 min read

How Social Media was Weaponized to Divide South Africans – The Tale of Bell Pottinger & The ‘Zuptas’

credit: The New Yorker; Illustration by Ben Jones In 2016, through various agents and representatives, scandalized former President Jacob...

Aug 5, 20259 min read

“Subscribe to PewdiePie” - How Internet Humour is leveraged to Encourage Fascism & Violence

In 2019, Brenton Tarrant - the Christchurch Killer - slaughtered 51 innocents and injured 89 others at two Mosques in Christchurch, New...

Jul 29, 20259 min read

Comments